Re-analyzing the Dr. Seuss study: context and comparative standards

The racism accusations against Dr. Seuss deserve closer examination. What does the research actually show? And how do his books compare to the children's literature of his era?

Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) is one of America's most beloved children's authors, known for imaginative classics like The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham. However, a 2019 study by Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens has scrutinized Seuss’s work for racist imagery and lack of diversity. In light of additional context, it’s important to analyze these findings with a true “apples-to-apples” standard, comparing Dr. Seuss’s portrayal of characters to those of other authors and the norms of his time, to assess whether he is being held to an unfair double standard.

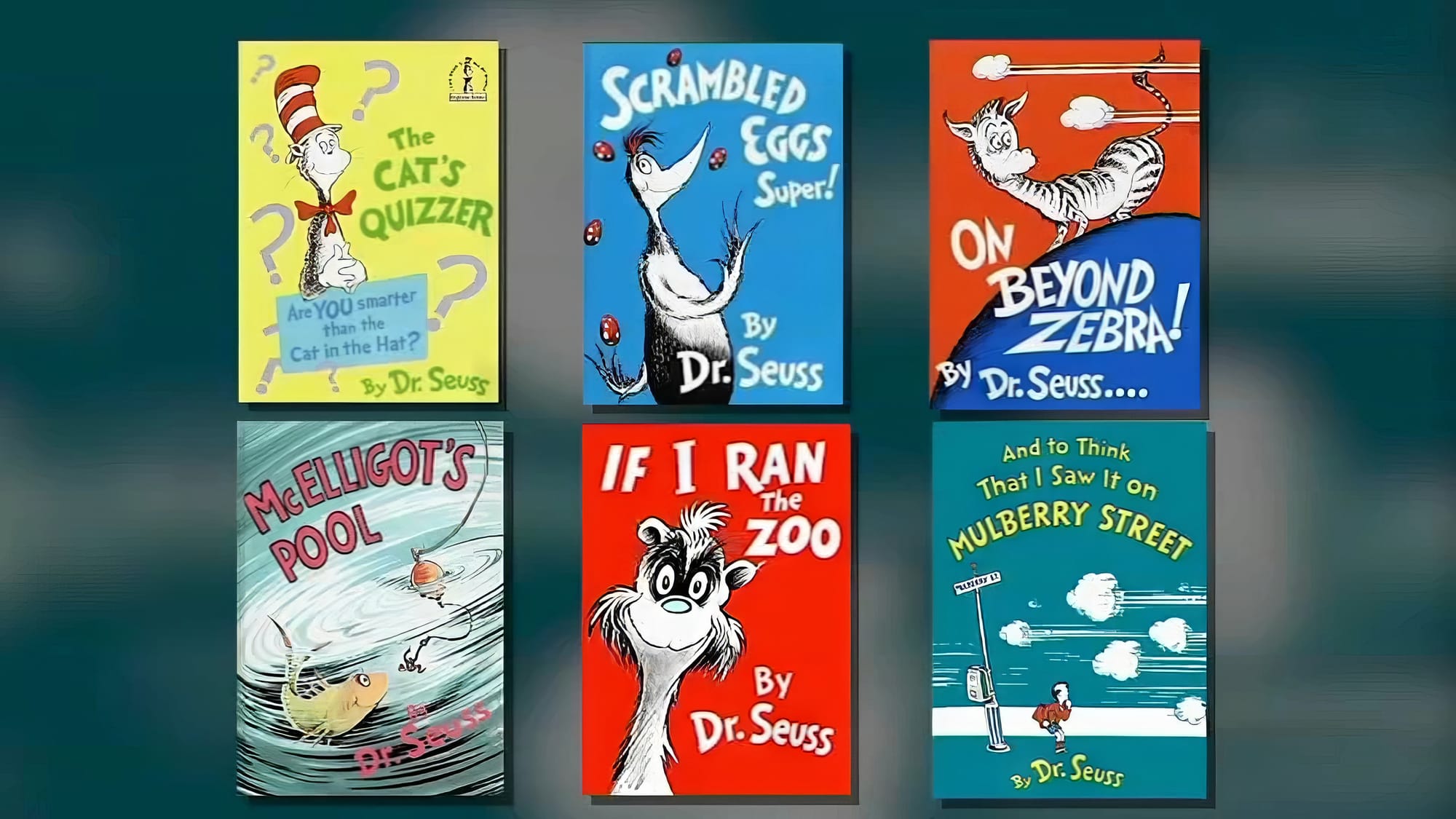

This research kicked the internet outrage machine into high gear and Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced in March 2021 they would no longer published six books because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong." The books were:

- And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937)

- If I Ran the Zoo (1950)

- McElligot’s Pool (1947)

- On Beyond Zebra! (1955)

- Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953)

- The Cat’s Quizzer (1976)

Was Dr. Seuss Enterprises right to do this? Let's look at the findings of the study.

Summary of the Study’s Findings

The Ishizuka & Stephens study, titled “The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss’s Children’s Books,” examined 50 of Dr. Seuss’s children’s books and with the following findings:

- Overwhelming Whiteness: The researchers counted 2,240 human characters across Seuss’s books, of which 98% are white. Only 2% (45 characters) are people of color. Notably, all 45 characters of color are male. There are no female characters of color in any of Seuss’s stories. White characters occupy 100% of the narrator and speaking roles in these books.

- Stereotyped “Others”: Every non-white character is portrayed in a stereotypical or demeaning way. The study found that “all of the characters of color were crafted in ways that reinforced Orientalism and anti-Blackness,” appearing “only in subservient, exotified, or dehumanized roles.” For example, in If I Ran the Zoo, a white boy protagonist speaks of using “helpers who all wear their eyes at a slant” and depicts Asian characters carrying him and his belongings, caricatured with slanted eyes and conical hats. The two African characters in that book are drawn as animal-like and subservient (barefoot, in grass skirts, carrying an exotic animal). Across Seuss’s works, characters of color never speak and are shown as servants, laborers, or curiosities controlled by white characters.

- Offensive Caricatures: Some of Seuss’s most famous books use non-human characters or fantasy creatures in ways that convey racist imagery. The study notes that The Cat in the Hat and other beloved stories contain allegories or character designs rooted in racial caricature (e.g. the Cat’s design drawing on blackface minstrel stereotypes). Additionally, Seuss’s earlier career as a political cartoonist produced blatantly racist depictions, for instance, anti-Japanese propaganda during WWII and ads with racist slurs. These historical drawings, while outside his children’s books, inform some of the stereotyped imagery that appears in the books (such as the exaggerated “Oriental” caricatures).

The authors of the study argue that such patterns are harmful. Children’s books help shape how kids understand the world; when nearly all heroes are white and people of color are either absent or shown in demeaning ways, it can reinforce racist attitudes and a sense of white superiority. In their words, “when children’s books center Whiteness, erase people of color and other oppressed groups, or present people of color in stereotypical, dehumanizing, or subordinate ways, they both ingrain and reinforce internalized racism and White supremacy.” This explains why educators and publishers today are questioning Dr. Seuss’s place in curricula and even pulling some of his titles from publication.

Are Seuss’s Critics Applying a Double Standard?

While the accuracy of the study’s findings isn’t in dispute (the numbers and examples are well-documented), a key question is whether Dr. Seuss is being held to a standard that has not been equally applied to other authors. Many supporters feel that Seuss is being unfairly singled out, “held to a standard that no other authors are being held to,” perhaps because he is a prominent white American male author. Several points support this perspective.

Historical Norms in Children’s Literature: Critics argue that Seuss’s books reflected the common practice of his era, rather than an extreme anomaly. In the mid-20th century, the vast majority of children’s books featured only white characters and Eurocentric settings. For example, educator Nancy Larrick’s landmark 1965 survey of children’s literature found that only 6.4% of American children’s books (1962–1964) included even a single Black character, meaning over 93% of books had zero representation of African Americans. Of those few books including Black characters, most were historical or folk tales, with fewer than 1% of books showing Black children in contemporary life.

This revealing statistic led Larrick to famously dub it “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” In this context, Seuss’s figure of ~2% characters of color across his works is sadly typical of the period. One longtime teacher-librarian noted that in her experience starting in the 1960s, “this was true of most books” at the time, nearly all protagonists were white, usually male. In other words, Dr. Seuss was conforming to the industry norm of his day, not uniquely deficient in diversity when compared to his contemporaries. By holding Seuss to today’s standards of diversity without similar scrutiny of other classic authors, the study could be seen as applying a retroactive double standard.

Majority vs. Minority Authors: The expectations placed on authors regarding representation have historically been asymmetrical. Authors from marginalized groups (for example, female authors or authors of color) have not been routinely expected to center characters outside their own identity group. In fact, it has been quite the opposite: there has been a push for more authentic voices and #OwnVoices stories, encouraging authors to write from their own cultural/gender experiences. For instance, no one demands that a Black children’s author include more white protagonists for “balance,” nor that a woman writing children’s books must feature more male leads, because traditionally the dominant culture’s perspective (white, male) was already over-represented in literature.

By contrast, white male authors like Dr. Seuss (who occupy a dominant cultural position) often face calls to include diverse characters and are criticized when they don’t. This imbalance in expectations can be viewed as a double standard. Women authors are not asked to write more about male characters, and Black authors are not asked to write more about White characters, yet Seuss is chastised for not portraying more women or people of color. The study’s authors explicitly criticize Seuss for centering whiteness and largely ignoring other groups, a critique that has not been equivalently applied to many other authors of his era who did the same.

Context of World War II Propaganda: Some of the most offensive images associated with Dr. Seuss come from his WWII-era political cartoons, in which he depicted Japanese people with grotesque, dehumanizing stereotypes (e.g. drawing them with fangs or as menacing reptiles, and using slurs). It’s crucial to note that war propaganda on all sides during WWII was routinely racist and dehumanizing toward the enemy. American government propaganda, as well as popular media of the 1940s, never portrayed Axis powers in a favorable or even humane light, nor did Axis nations portray Allied peoples any better. In this sense, expecting Dr. Seuss’s 1940s cartoons to have been free of anti-Japanese sentiment would be as unrealistic as expecting a government to produce flattering portrayals of its wartime enemy.

History shows no example of, say, the U.S. government commissioning positive, empathetic depictions of Japanese or German people in the middle of WWII, quite the contrary, the propaganda goal was to vilify the enemy. Dr. Seuss, as a cartoonist for the liberal PM newspaper, was actually more progressive than many peers on some issues (he lambasted Hitler’s fascism and even criticized American segregation policies in a few cartoons), but he shared in the era’s anti-Japanese racism fueled by the war. None of this excuses those racist drawings, they are unquestionably offensive, it just underscores that Seuss was operating within the same framework as others in his position. Singling him out without acknowledging that broader context could be seen as applying a harsher standard to him than to others who produced similar wartime propaganda. In short, no government or media of the time was “writing favorably about the enemy,” so expecting that of Seuss alone would be inconsistent with the historical norm.

In light of these points, supporters of Dr. Seuss argue that the study’s authors may have judged him by criteria that weren’t applied universally. They suggest that because Seuss is a high-profile white male figure in children’s literature, his works are under the microscope in a way that others’ works have not been. The charge of “white supremacy” in his book, for example, might imply personal malice or singular culpability, when in reality his books’ racial imbalance was essentially the default state of the genre for decades. This doesn’t mean the findings are untrue, but it raises the question of fairness: Was Dr. Seuss notably worse in representation, or is he chiefly being called out because his books remain hugely popular today?

The Need for Data and Apples-to-Apples Analysis

To determine whether a double standard is at play, comparative data is critical. Rather than evaluating Dr. Seuss in isolation, we should look at how his work compares to other authors and publishing trends, both in his era and even today. Fortunately, some comparative insights are available.

A recent Education Week article noted that a lack of non-white characters is “not a feature unique to Dr. Seuss books,” surveys of children’s literature throughout the years have consistently found that Black, Latino, Asian, and Indigenous characters are underrepresented in kids’ books. For example, even in 2018-2019, only about 11–12% of children’s books in the U.S. had Black characters, around 8–9% had Asian characters, etc., according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center statistics. This shows that diversity in kids’ books has been historically low across the board, though it’s slowly improving. Dr. Seuss’s 2% characters of color was low, but many mid-century authors had 0–1% and often none at all. His works were not singular outliers in that regard, though the sheer fame of his books makes the impact of their biases more significant.

If we take “apples-to-apples” comparisons, we’d compare Seuss’s books to other children’s classics of similar vintage. Consider mid-century picture books by other famous authors: How many characters of color appear in the works of, say, Margaret Wise Brown (author of Goodnight Moon), C.S. Lewis (Chronicles of Narnia), Laura Ingalls Wilder (Little House series), or E.B. White (Charlotte’s Web)? The answer in almost every case is very few or none, and in some cases, when non-white characters do appear, they are often depicted in stereotypical ways consistent with the attitudes of the time. Yet, while Wilder’s depictions of Native Americans or some of Roald Dahl’s early writings have faced criticism, no other children’s author of Seuss’s era has been as thoroughly examined for overall character demographics as Seuss was. This suggests the scrutiny is disproportionately focused on Seuss, likely because his brand is so visible in schools (e.g. Read Across America Day was long tied to Seuss’s birthday) and because society is currently re-evaluating longstanding icons.

Comparative data can also be applied to the gender representation in children’s books. Historically, male characters (and authors) dominated children’s literature, but we generally do not see people faulting a female author for writing stories centered on girls, or demanding that she include more boys. In fact, studies show that female authors in recent decades often do include more female protagonists (helping address a prior imbalance). This is seen as a positive corrective, not a flaw. By analogy, authors of color often write about their own communities, which is welcomed as authentic representation, not criticized as exclusion of white characters.

These comparisons reinforce that it’s typically those in the majority who are asked to diversify their content, whereas those in the minority are not asked to do the reverse. In the case of Dr. Seuss, being a white male author in a very homogeneous literary canon makes him an obvious target for calls to diversify (posthumously). But we found no evidence of any author from a marginalized group being admonished for centering their own group. This lack of a “reverse” expectation underscores the one-sided nature of representation criticism. It’s essentially expected that authors will write from their own cultural standpoint; only when that leads to systemic exclusion (as with an all-white industry) do critics step in, and those critics have focused on mainstream (mostly white) creators.

Given these findings, comparative analysis supports the idea that a double standard has been applied to Seuss, at least in the sense that his works are judged by a benchmark of diversity that few (if any) of his peers met at the time. Unless we can point to examples of other authors from different demographics being held to the same benchmark, which, based on my research, such examples are virtually nonexistent, it appears that Seuss’s critics are indeed using a special lens for him. We did not find any counter-examples where, say, a Black children’s author was criticized for not including white characters, or a female author was pressured to include more male characters. Nor do we find instances of wartime artists praised for positive depictions of enemy nations. The absence of such analogues reinforces that Seuss’s case is somewhat unique.

Conclusion

The 2019 Ishizuka & Stephens study illuminates problematic aspects of Dr. Seuss’s oeuvre, the near-erasure of people of color, and the stereotyped portrayals of the few that appear, are well-supported by the data. These findings raise valid concerns about what messages children absorb from these classics. However, adding the context of historical norms and comparative standards complicates the picture. Dr. Seuss was not an outlier among 20th-century authors in centering white characters; he was a product of a time when children’s literature in America was overwhelmingly white by default. The double standard emerges when we ask: Why focus on Seuss’s 98% white characters as evidence of “white supremacy” if virtually all his contemporaries had similar breakdowns? The answer may lie in his enduring prominence and the evolving values of our society, we now expect better from books we give to children. As one article noted, “children of all backgrounds should see themselves in the books that they read,” a principle that has driven initiatives to spotlight diverse books in place of the usual Seuss-centric celebrations.

In re-analyzing the study with an apples-to-apples approach, we find that Seuss is being judged by today’s ideals in isolation, rather than in direct comparison to others. This doesn’t invalidate the critique of racism in his books, it simply reminds us that he was not uniquely guilty, just uniquely famous. Moving forward, it’s reasonable to continue critically examining Seuss’s legacy (as his own estate has done by ceasing publication of six offensive titles). But it’s also important to recognize that the lack of diversity in Seuss’s books was a systemic issue of his era, not a deliberate outlier. A fair, “apples-to-apples” standard would mean applying the same critical lens across the board. By that measure, virtually the entire mid-century children’s literature canon would be found wanting. Not just Dr. Seuss.

Some Question for Future Research

I think the author’s structural racism argument points to the real target: publishers, not individual authors. Publishers are the ultimate gatekeepers of publishing standards. For example, how many authors submit manuscripts each year, broken down by race and gender? Of those, how many are published? It is easier to go after single individuals because that will not provoke the wrath of large corporations or threaten the structure of the overall system.

The Conscious Kid helped fund the research by Stephens and Ishizuka. The nonprofit’s president is Katherine “Katie” Ishizuka and its executive director is Ramón Stephens. In 2018, before the publication of this paper, their budget was under $50,000. According to the most recent publicly available IRS Form 990 filings, Dr. Ramón Stephens earns about $135,000 annually from The Conscious Kid, and Katherine Ishizuka earns about $125,000. Good, hard work deserves to be rewarded, but those are healthy nonprofit salaries, especially given the organization’s rapid growth from a sub-$50k budget just a few years earlier.

To accomplish The Conscious Kid’s mission, Stephens and Ishizuka also need to work with and influence publishers, both big and small. Publicly criticizing publishers is unlikely to help them achieve that goal. Even the most noble missions can be warped by financial incentives. Be skeptical of even the most altruistic-looking motives. We all have an agenda.