Self-preservation above all else: when the 1st law breaks

Real-life acts of self-sacrifice, from Nicholas Bostic's fire rescue to 9/11 heroes, examined through Schopenhauer and Joseph Campbell on unity and when self-preservation dissolves.

We grow up believing the first law of nature is ironclad: keep yourself alive. It is supposed to hum quietly under every decision and every instinct. But sometimes, in a flash, that law just is not there. Someone hurls themselves into danger for another person, not a child they raised, not a spouse, sometimes not even a name they know. In an instant, the whole structure of self-preservation collapses.

One summer night in Lafayette, Indiana, a 25-year-old pizza delivery driver named Nicholas Bostic was heading home. A house caught his eye. Not the house itself, but the glow of fire. Inside were five people: an 18-year-old woman, her two younger sisters, a toddler, and another child. Bostic went in through the back door, found four of them, and brought them out. That could have been the end of it. A job well done.

It was not. Outside, he heard there was still a 6-year-old inside. Back in he went.

"If opportunity came again and I had to do it, I would do it. I knew what I was risking. I knew the next second it could be my life. But every second counted." - Bostic told ABC News

By then the place was collapsing. An explosion on the porch had spread the fire faster than anyone expected. Upstairs the air was almost gone. Heat pressed in from every direction. Somewhere below, a voice cried out. He found the girl near the living room, scooped her up, and headed back up the stairs into another burning room. There, he smashed a window with his bare hand, climbed through, and jumped two stories with her in his arms. They both lived. Bostic spent three days in the hospital with smoke inhalation, burns, and a deep arm wound. She went home with her family. Why?

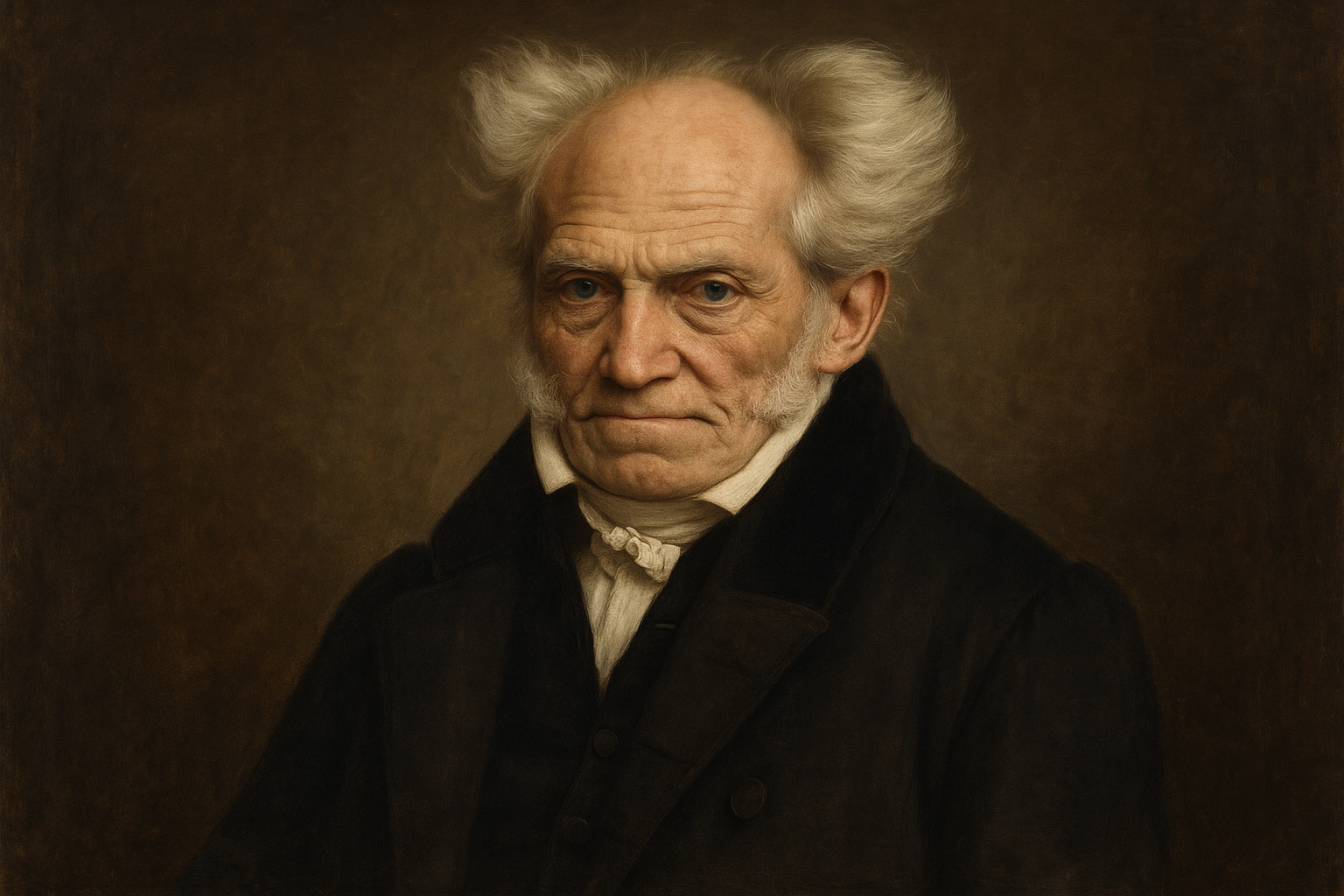

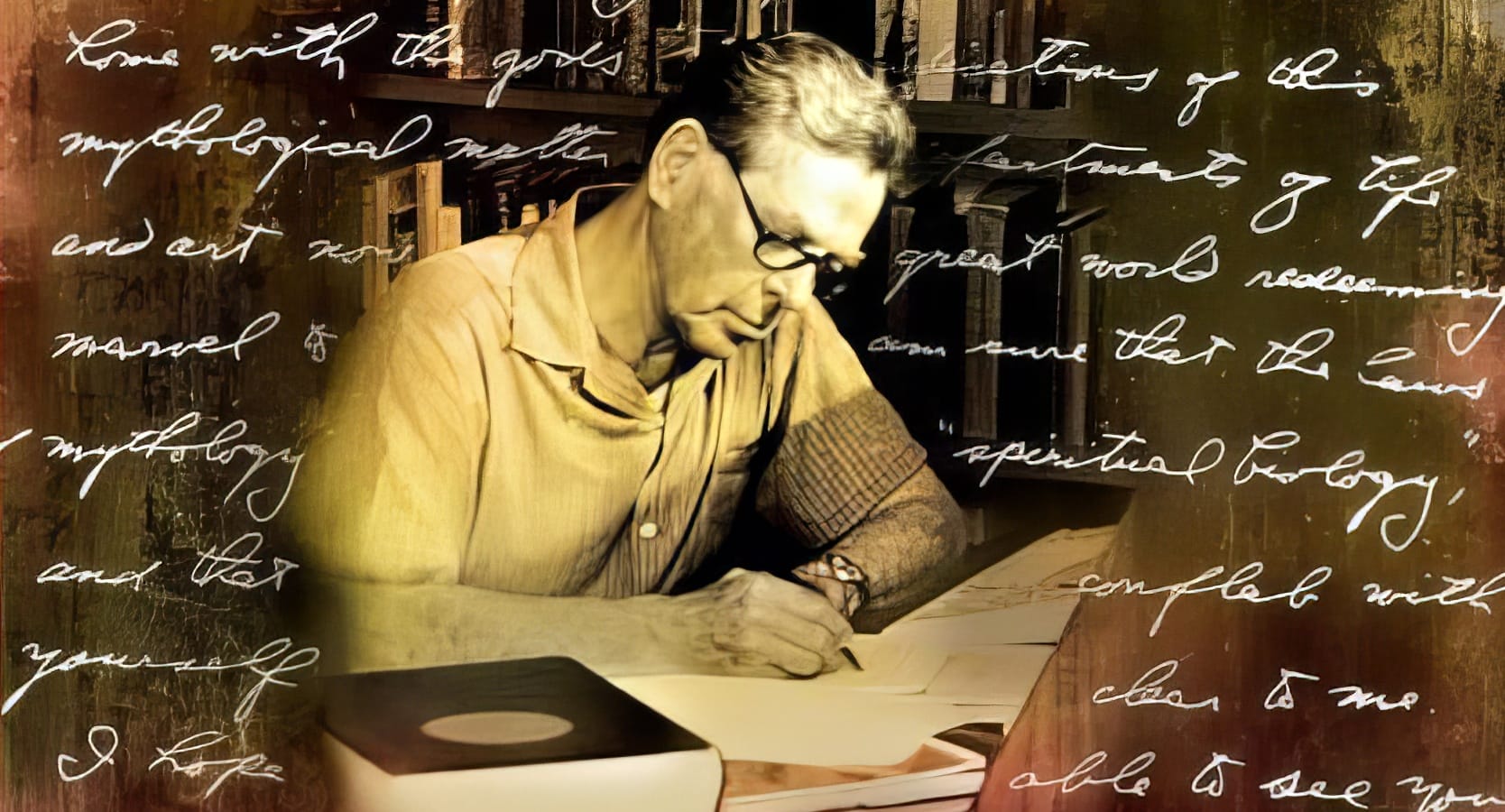

Schopenhauer’s Puzzle

Arthur Schopenhauer, in The Basis of Morality, spends pages circling a question he cannot quite let go of. What makes someone throw themselves into another person’s peril so completely that their own safety vanishes from thought? How does the instinct to stay alive, the one we usually imagine as the very root of life, disappear in a moment?

He does not find his answer in rules or agreements. It is not a moral duty calculated in advance, and it is not a bargain where help is traded for future help. He points to compassion, but not the soft, polite kind. This is compassion as a kind of vision shift, where the line between self and other is gone. Another person’s suffering is not observed, it is felt as your own. When that happens, the usual machinery of self-interest is no longer in the room.

If you read Bostic’s rescue through that lens, it stops looking like a decision. His drive to live was, for those minutes, no different from the child’s drive to live. There was no weighing of consequences. No “what happens if I fail.” Only movement.

Joseph Campbell tells a story in The Power of Myth that gets at the same thing from another angle. The setting is the Nuʻuanu Pali Lookout on Oʻahu, a cliff pass where the wind can shove you sideways and the view can pull your gaze all the way out to the sea. In 1795, it was the site of the Battle of Nuʻuanu, where King Kamehameha I’s forces drove enemy warriors over the edge in the final push to unite the Hawaiian Islands.

Today, tour buses stop there for the panorama. It has also been the end point for people who no longer wanted to live.

One day, two policemen came upon a young man ready to jump. One officer lunged and caught him in mid-air, and in that same instant felt himself being pulled toward the drop. His partner arrived just in time, grabbing both and pulling them back onto solid ground.

When reporters later asked why he had not let go, the officer said, “I could not. If I had, I could not have lived another day of my life.” In Campbell’s reading, that was the moment when everything else, including the officer’s duties, his family, and his own survival, simply dropped away. There was only the connection between him and the man he was holding.

Schopenhauer would say that in that instant, the division between them was gone. What was left was unity.

Bostic’s second trip into the burning house stands out because it came after he already knew how bad it was. He had seen the smoke, felt the heat, and understood how close the place was to collapse. The first entry could be chalked up to impulse or ignorance. The second was done in full knowledge of the risk.

The same is true in the Pali story. The officer could have reasoned it out. The attempt was dangerous, the odds were poor, and the man might have wanted to die. Instead, he simply could not let go. These moments do not run through the brain’s flowchart. They seem to come from someplace underneath it.

A Pattern Across Time and Place

This is not unique to one night in Indiana or one cliff in Hawaii. On September 11, 2001, thousands of people were trying to escape the burning towers in New York. Others were going the opposite way.

Welles Crowther, remembered as “the Man in the Red Bandana,” worked on the 104th floor of the South Tower. He led groups of strangers down the stairwells, carried an injured woman over his shoulder, then turned around and went back up. He kept doing this until the tower came down.

Rick Rescorla, head of security for Morgan Stanley, had spent years running evacuation drills. When the South Tower was hit, he took a bullhorn and moved from floor to floor, steadying people with calm orders and even singing to keep panic down. He got more than 2,500 people out before heading back in himself.

Frank De Martini and his team — Pablo Ortiz, Peter Negron, Carlos da Costa — were on the 88th floor of the North Tower when the first plane hit. They forced open blocked stairwells, pried elevator doors, and led dozens to safety. They kept climbing, rescuing more, until the building fell.

FBI Special Agent Leonard Hatton was on his way to work when he saw the smoke. He joined the firefighters heading in, guiding evacuations, and moving toward the impact floors. He never came out.

FDNY Battalion Chief Orio Palmer reached the 78th floor impact zone of the South Tower, climbing through heat and debris with gear on his back. His voice was still calm on the radio minutes before the collapse.

There were also those not assigned there at all. Former Marines Jason Thomas and Dave Karnes converged on the site, searched the wreckage, and pulled two trapped Port Authority officers out alive.

Every one of these moments looks the same through Schopenhauer’s lens. The wall between self and other disappears. There is no talk of rewards and no pause to assess survival odds. The unity is direct.

It can happen to anyone. A delivery driver. A police officer. A trader in a suit. A fire chief. A passerby. The unsettling part is not that it happens, but how rarely. Maybe we do not often face situations that would pull us across that boundary. Or maybe the unity itself is too brief and too fragile to live in for long.

Campbell’s Amplification

Campbell takes it further. In myths, the hero crosses a threshold where the old self dies, sometimes literally, and something new returns. In real life, the shift might last minutes. But in that time, the person lives in a different order of reality. Their life is no longer something they “own” in the usual way.

Seen that way, the firefighter climbing toward a burning floor and the stranger diving into a frozen river are doing the same thing the mythic hero does. They cannot refuse the call without shattering themselves.

Afterward, we wrap these acts in familiar forms such as medals, ceremonies, and news features. It makes them fit our moral economy. Courage is rewarded. Sacrifice is honored. Social cohesion is affirmed.

The act itself, as Schopenhauer notes, may have nothing to do with those systems. It happens before duty and before law.

Some survivors carry it quietly. Rescorla’s widow has spoken about the years of preparation behind his final moments. The people Crowther saved meet every year to honor him. The Hawaiian officer probably never wanted a public story in the first place.

Why This Matters

It is easy to think every self-sacrifice is noble. History says otherwise. People have given their lives for causes later revealed as corrupt or hollow.

Schopenhauer’s compassion is different. It responds to the reality of another’s suffering right in front of you. No ideology. No abstraction. The moral force comes from that immediacy.

In a culture that prizes individualism and guarding one’s own, these stories cut against the grain. They show the capacity for unity is still there, even if dormant. The challenge is whether we can touch it without waiting for disaster. Campbell put it this way:

...such a psychological crisis represents the breakthrough of a metaphysical realization, which is that you and that other are one, that you are two aspects of the one life, and that your apparent separateness is but an effect of the way we experience forms under the conditions of space and time. Our true reality is in our identity and unity with all life. This is a metaphysical truth which may become spontaneously realized under circumstances of crisis. For it is, according to Schopenhauer, the truth of your life. The concept of “love your neighbor” is to put you in tune with this fact. But whether you love your neighbor or not, when the realization grabs you, you may risk your life.

Most of us will never be in a burning building or on the Pali in that exact moment. Yet there are smaller echoes: stepping in to stop harassment, pulling someone back from the curb as a car speeds past, or donating blood without knowing the recipient. These are also moments when self-interest loosens its grip. Schopenhauer would put them on the same line as the bigger, rarer acts.

Bostic lived. The girl lived. The Hawaiian officer and the young man lived. Many on 9/11 did not, though countless more did because someone ran toward danger.

The question that lingers is not about the outcome. It is about the moment itself, the transformation. If the unity of life can feel so real in crisis, why does it fade so easily in calm? And if it found you, would you go in the second time?