The Widening Chasm Between Business and Technology

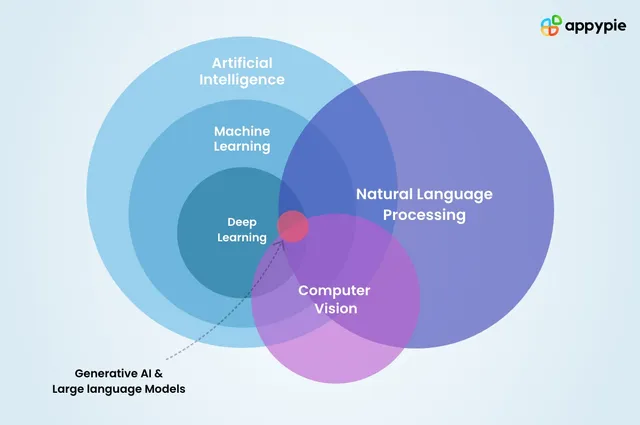

Top MBA programs still underprepare business leaders for the data and AI-driven economy. Meanwhile, tech teams are losing architectural discipline. This article explores the root causes of the disconnect and offers actionable steps to rebuild alignment between business and technology leaders.

In today’s business environment, where strategy, operations, and innovation are increasingly shaped by data and technology, the gap between business and technology leadership has become glaring. Many business leaders still make decisions without a real grasp of how data systems or models work. Meanwhile, many technology teams have dropped the discipline and structure once considered essential to building scalable, understandable, and trustworthy systems.

What we’re witnessing is not just a miscommunication between two functions. It’s a growing structural and cultural divide. I would like to explore how we got here, how the education pipeline and organizational practices contributed to the disconnect, and what can be done to close the gap.

The Business Education Blind Spot

Let’s begin with the training ground for most business leaders: top MBA programs. While these institutions have evolved in many areas, the core curriculum at many still emphasize domains like finance, accounting, marketing, strategy, and leadership. These are critical, but they now represent only part of the picture.

I looked at the required core curriculum, not electives, at five leading MBA programs: Harvard, Wharton, MIT Sloan, Chicago Booth, and Stanford GSB. To make this digestible, I focused on a handful of categories and assigned simple weights: 1.0 for a full course, 0.5 for partial or blended coverage.

| School | Finance | Strategy | Leadership | Marketing | Statistics | Data/Tech | Ethics | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvard (HBS) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Wharton | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| MIT Sloan | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Chicago Booth | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Stanford GSB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Even as data, AI, and software reshape every function in business, these topics remain underrepresented. Most graduates get a single statistics course and, in many cases, nothing on how modern data or technology systems actually work. Wharton’s forthcoming AI and analytics focus is promising, but it’s optional. Why?

The Erosion of Technical Discipline

It would be easier to accept this gap if technology teams made up the difference. They used to. At one time, data professionals and system architects began their work with design. They modeled domains, captured requirements, and debated definitions before writing any code. That mindset has faded.

Today, Jira tickets often stand in for real design.

Today, Jira tickets often stand in for real design. Systems are built by reverse-engineering data that already exists. Documentation is rare, and when it exists, it’s mostly written after the fact. Engineers work from vague direction and piece together pipelines that may function mechanically but fall apart semantically.

Agile development, while well-intentioned, contributed to this. It was meant to support fast iteration and customer input. Instead, it often turned into an excuse to skip planning. Combined with modern data tools that enable quick deployment, rigor started to look like friction.

The irony is that skipping structure creates more work. Teams spend more time redoing things. Metrics lose credibility. Dashboards become suspect. Analysts chase down logic instead of building insights. People trust their intuition over the reports in front of them.

The Cost of Misalignment

What you get when both business and tech abandon depth is a dangerous feedback loop. Business leaders assume the data is sound. Tech teams assume the requirements are clear. The output looks good on the surface, but the foundation is weak.

KPI definitions don’t match between teams. Metrics that seemed stable last quarter behave differently this quarter. A dashboard makes sense until someone explains how the calculations work. The data model captures part of the business, but not the part that matters for the current decision.

Even when people want to collaborate, they talk past each other. The business talks in goals. The tech side talks in fields, joins, and tables. In between, a lot gets lost.

What Needs to Change

To move forward, the expectations for both sides need to evolve. Business leaders need to engage with how data and technology actually work. Not at a deep engineering level, but enough to reason about what’s reliable, what’s changing, and what’s worth questioning.

That means understanding things like sample sizes, confidence intervals, how pipelines are built, and why metric definitions require precision. It also means being involved in metric reviews and product design conversations, not just showing up at the end to approve the slide deck.

Technology leaders, in turn, have to restore discipline. That starts with treating design as real work. Not just database structure, but how the business actually thinks about customers, transactions, or outcomes. If a column says “user_id,” what kind of user is it? If a metric says “churn,” does that mean canceled? Paused? Inactive?

Modeling these ideas clearly before building ensures that what’s built serves a purpose and can be trusted. Code can move fast, but clarity only comes from shared thinking.

Getting Fluent Again

The goal isn’t for everyone to be a data scientist or systems architect. It’s for leaders across functions to share a language. That means business people who can ask good technical questions and technical people who understand business priorities.

A product manager should be able to challenge a model’s assumptions. A CFO should understand the data lineage behind financial metrics. A data engineer should be able to explain what revenue means in different business contexts.

That kind of fluency can’t be outsourced. It has to be built and rebuilt over time, through how we educate future leaders and how we operate today.

Sources: